I love Ramit's blog and what he finds. Here's the article that he found and track from studyhack: Time management: How an MIT postdoc writes 3 books, a PhD defense, and 6+ peer-reviewed papers — and finishes by 5:30pm

Quote below:

I’m always on the lookout for “hidden gems,” or people who are doing remarkable work that the whole world hasn’t caught on to, yet.

Today, I asked my friend Cal Newport to illustrate how he completely dominates as a post-doc at MIT, author of multiple books, and popular blogger. How does he do it all?

Cal writes one of the best blogs on the Internet: Study Hacks. His guest post shows how you can take I Will Teach You To Be Rich principles — plus many others — and integrate them into a way to use your time effectively.

Below, you’ll learn:

- How to use fixed-schedule productivity — similar to the Think, Want, Do Technique — to consciously choose what you want to work on and ignore worthless busywork

- When to say no — and how to do it

- How a $60,000-a-speech professional manages his time

- Case study: How to use email for maximum time productivity

Read on.

From Cal:

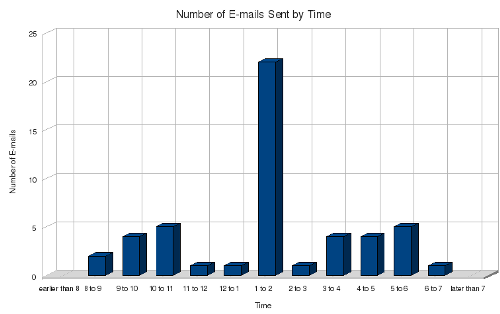

I recently conducted a simple experiment: I recorded the timestamps of the last 50 e-mails in my sent messages folder. These timestamps covered one week of my e-mail behavior, starting on Thursday, October 22nd and ending Thursday, October 29th.

My interest was to measure when during the day I spent time on e-mail. Here’s what I found:

Notice that over this week-long period, I didn’t send any e-mail after 7:00 pm, and only one e-mail after 6:00 pm. There’s a good explanation for this discipline: I end all work around 5:30 every day. No Internet. No computer. No to-do lists. Once I shutdown my day, it’s time to relax.

I must emphasize that I’m not some laid-back lifestyle entrepreneur who monitors an automated business from a hammock in Aruba. I have a normal job (I’m a postdoc) and a lot on my plate.

This past summer, for example, I completed my PhD in computer science at MIT. Simultaneous with writing my dissertation I finished the manuscript for my third book, which was handed in a month after my PhD defense and will be published by Random House in the summer of 2010. During this past year, I also managed to maintain my blog, Study Hacks, which enjoys over 50,000 unique visitors a month, and publish over a half-dozen peer-reviewed academic papers.

Put another way: I’m no slacker. But with only a few exceptions, all of this work took place between 8:30 and 5:30, only on weekdays. (My exercise, which I do every day, is also included in this block, as is an hour of dog walking. I really like my post-5:30 free time to be completely free.)

I call this approach fixed-scheduled productivity, and it’s something I’ve been following and preaching since early 2008. The idea is simple:

- Fix your ideal schedule, then work backwards to make everything fit — ruthlessly culling obligations, turning people down, becoming hard to reach, and shedding marginally useful tasks along the way.

The beneficial effects of this strategy on your sense of control, stress levels, and amount of important work accomplished, is profound.

The notion is not new. Tim Ferriss famously recommend strict time constraints in The 4-Hour Work Week. He argued that much of the work we do is of questionable importance and conducted at low efficiency. (He made a popular — if not somewhat dubious — appeal to Parkinson’s Law to support the point that more time does not necessarily lead to more results.) If we instead identify only the most important tasks, he said, and tackle them under severe constraints, we’d be surprised by how little time we actually require.

In this article, I want to tell the stories of real people who successfully implemented this strategy – radically improving the quality of their lives without scuttling their professional success.

Jim Collins’ Whiteboard

Jim Collins has sold over seven million copies of his canonical business guides, Good to Great and Built to Last. He attributes the success of these books to his research discipline. As he revealed in a New York Times profile from last May, he leads teams of up to a dozen undergraduates in the process of information gathering. His books require, on average, a half-decade of time and a half-million dollars of expenses to get from their initial premise to the polished ideas. When he enters his “monk” mode to covert this research into a manuscript, he produces, at best, a page a day.

In other words, Collins is a hardworking guy. You would expect, therefore, that like many hard-charging business-world types he would be a blackberry-by-the-bedside workaholic.

But he’s not.

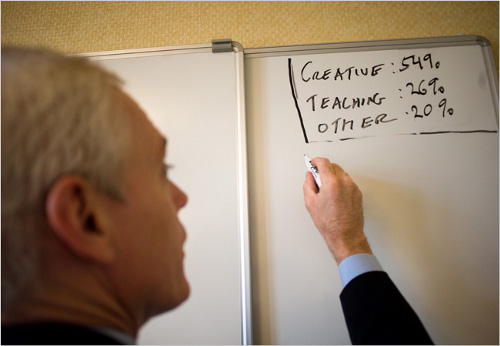

Scrawled on a whiteboard in the conference room of Collins’ Boulder, Colorado office is a simple formula:

Creative 53%

Teaching 28%

Other 19%

Collins decided years ago that a “big goal” in his life was to spend half of his working time on creative work — thinking, researching, and writing — a third of his time on teaching, and then cram everything else into the last 20%. The numbers on the whiteboard are a snapshot of his current distribution. (He tracks his time with a stop watch and monitors his progress in a spreadsheet.)

Collins is a pristine example of fixed-schedule productivity in action. An author with his level of success could easily fall into an overwork trap: long nights spent updating twitter, signing partnerships, building elaborate web sites and launching product lines, speaking at every possible venue. But he avoids this fate.

Even though Collins demands over $60,000 per speech, for example, he gives fewer than 18 per year, and a third of these are donated for free to non-profit groups. He doesn’t do book tours. His web site is mediocre. He keeps his living expenses in check so that he’s not dependent on drumming up income (he and his wife have lived in the same California bungalow for the past 14 years), and he keeps only a small staff, preferring to bring on volunteers as needed.

“Mr. Collins…is quite practiced at saying ‘no,’” is how The Times described him. (He once wrote an article for USA Today titled: “Best New Years Resolution? A ‘Stop-Doing’ list.”)

His fixed-schedule approach to life comes from his simple conviction “to produce a lasting and distinctive body of work,” and his “willingness…to focus on what not to do as much as what to do” has made that possible.

He’s not alone in reaping the benefits of the fixed-schedule approach…

Elizabeth’s Conversion

When Elizabeth Grace Saunders started her first business, a professional copy-writing service, her schedule has “hazardous.”

“I would answer e-mails after going out with friends,” she told me, “and stay up until 2 a.m. finishing projects.”

At some point, she snapped. “I’m not a secretary,” she declared. “I’m not required to jump to respond to everything that crosses my path.”

Saunders adopted a 40-hour a week schedule. This new structure had two immediate impacts. First, she found herself focusing only on the most important tasks. With only a few hours to spare on business development, for example, she couldn’t justify wasting time with the small, ineffectual website tweaks and exploratory e-mails that used to keep her up late into the night. Instead she focused on the core activities that produced results, such as sales calls or the development of new products. The focus generated by this constraint ended up generating more results than her previous schedule, which was more expansive, but also more scattered.

The second impact was her discovery that she could teach her clients how to treat her.

“I’ll answer your e-mail within 24 hours (not 24 minutes), I need notice before starting a project, I will say ‘no’ if my schedule for the near future is already full, and I might schedule meetings up to a month in advance.”

“Choosing how and when I respond to requests has had a dramatic impact,” Saunders notes.

Friends and clients were impressed enough with Saunders’ lifestyle that she eventually left copywriting to become a “time coach” that works with other women in business to achieve similar results. (Her flagship service is called a Schedule Makeover.)

Here’s a typical day in Saunders’ life:

- She’s up at 6 and by 8:30 she’s at the computer.

- The first 1 – 2 hours of her work day are spent doing what she calls “routine processing,” which includes checking calendars, clearing e-mail inboxes, and cementing a plan to follow for the rest of the day. As Saunders describes it, this morning routine prevents her from wasting time deciding how to start, and it frees her of the “compulsion” to be checking e-mail throughout the day.

- She continues with an hour of sales calls. This is often the most dreaded activity for the solo entrepreneur. But by having a regular place in her constrained schedule, she avoids pushing it aside.

- The rest of the day follows the schedule she fixed in the morning: usually a mix of client assignments and at least one business development activity.

- By 5:30 she’s done.

Most entrepreneurs work well past 5:30 (and claim that this is absolutely unavoidable), but Saunders’ business is thriving. The reason is clear: her fixed schedule forces her to do the work that produces results (sales calls, client assignments, major business development activities) and eliminates the hours of pseudowork that many use to fill their day in an effort to feel “busy” (tweaking websites, compulsive e-mail checking, chasing down small business development opportunities).

Saunders is not the only young entrepreneur I’ve met who was surprised to discover that doing less helped the bottom line…

The Baby Factor

Michael Simmons, a good friend of mine, reported a similar story. His company, the Extreme Entrepreneurship Education Corporation, expanded quickly in the years following college graduation. Around the time I was reading The 4-Hour Work Week, I started to discuss the possibility that Simmons tone down the hours. It was his company, I argued, so why not take advantage of this fact to craft an awesome life.

Among the specific topics we discussed, I remember suggesting that Simmons cut down the time spent on e-mail and social networks.

“This isn’t optional for me,” he explained. “Any of these contacts could turn into a important partner or sale.”

But then Simmons’ daughter, Halle, was born.

Simmons’ work schedule reduced from 10 to 12 hours days to 3 to 5 hour days. He took care of the baby in the morning, then worked in the afternoon while his wife, and company co-founder, took over the childcare responsibilities. Evenings were family together time.

Halle forced Simmons into the type of constrained schedule that he had previously declared impossible. And yet the business didn’t flounder.

“The baby turns ’shoulds’ into ‘musts’,” Simmons explained to me. “In the past I used to put off key decisions, or saying ‘no’, because I didn’t want to deal with the discomfort. Now I have no choice. I have to make the decisions because my time has been slashed in half.”

“Since out daughter was born about a year ago, our business has more than doubled.”

The Fixed-Schedule Effect

Collins, Saunders, and Simmons all share a similar discovery. When they constrained their schedule to the point where non-essential work was eliminated and colleagues and clients had to retrain their expectations, they discovered two surprising results.

First, the essentials — be it making sales calls, or focusing on the core research behind a book — are what really matter, and the non-essentials — be it random e-mail conversations, or managing an overhaul to your blog template — are more disposable than many believe.

Second, by focusing only the essentials, they’ll receive more attention than when your schedule was unbounded. The paradoxic effect, as with Collins’ bestsellers, or Saunders and Simmons’ fast-growing businesses, you achieve more results.

Living the Fixed-Scheduled Lifestyle

The steps to adopting fixed-schedule productivity are straightforward:

- Choose a work schedule that you think provides the ideal balance of effort and relaxation.

- Do whatever it takes to avoid violating this schedule.

This sounds simple. But of course it’s not. Satisfying rule 2 is non-trivial. If you took your current projects, obligations, and work habits, you’d probably fall well short of satisfying your ideal schedule.

Here’s a simple truth that you must confront when considering fixed-schedule productivity: sticking to your ideal schedule will require drastic actions. For example, you may have to:

- Dramatically cut back on the number of projects you are working on.

- Ruthlessly cull inefficient habits from your daily schedule.

- Risk mildly annoying or upsetting some people in exchange for large gains in time freedom.

- Stop procrastinating.

In the abstract, these are all hard goals to accomplish. But when you’re focused on a specific goal — “I refuse to work past 5:30 on weekdays!” — you’d be surprised by how much easier it becomes to deploy these strategies in your daily life.

Let’s look at one more example…

Case Study: My Schedule

My schedule from my time as a grad student provides a good case study. To reach my relatively small work hour limit, I had to be careful about how I approached my day. I saw enough bleary-eyed insomniacs around here to know how easy it is to slip into a noon to 3 a.m. routine (the infamous “MIT cycle.”)

Here are some of the techniques I regularly used to remain within the confines of my fixed schedule:

- I’m ruthlessly results oriented. What’s the ultimate goal of a graduate student? To produce good research that answers important questions. Nothing else really matters. For some of my peers, however, their answer to this metaphysical prompt was: “work really long hours to prove that you belong.” It was as if some future arbiter of their future was going to look back at their time clock punch card and declare whether they sufficiently paid their dues. Nonsense! I wanted to produce a few good papers a year. Anything that got in the way of this goal was treated with suspicion. This results-oriented vision made it easy to keep the middling crap from crowding my schedule.

- I’m ultra-clear about when to expect results from me. And it’s not always soon. If someone slips something onto my queue, I make an honest evaluation of when it will percolate to the top. I communicate this date. Then I make it happen when the time comes. You can get away with telling people to expect a result a long time in the future, if — and this is a big if — you actually deliver when promised. Long lead times allow to you to side step the pile-ups (which will bust a fixed-schedule) that accrue when you insist on an immature, “do things only when the deadline looms” attitude.

- I refuse. If my queue is too crowded for a potential project to get done in time, I turn it down.

- I drop projects and quit. If a project gets out of control and starts to sap too much time from my schedule, or strays from my results-oriented vision: I drop it. If something demonstrably more important comes along, and it conflicts with something else in my queue, I drop the less important project. Here’s a secret: no one really cares what you do on the small scale, or what things you quit. In the end you’re judged on your results. If something is hindering your production of the important results in your field, you have to ask why you’re keeping it around.

- I’m not available. I often work in hidden nooks of the various libraries on campus, or from my apartment. I check and respond to work e-mail only a couple times a day, and never at night or on weekends. People have to wait for responses from me. It’s often hard to find me. Sometimes people get upset when they send me something urgent on Friday night that need done by Saturday morning. But eventually they get over it. Just as important, I’m not a jerk about it. I don’t have sanctimonious auto-responders about my e-mail habits. I just do what I do, and people adapt.

- I batch and habitatize. Any regularly occurring work gets turned into a habit — something I do at a fixed time on a fixed date. For example, I work on my blog in the afternoon after lunch. I write first thing in the morning. When I was taking classes, I had reoccuring blocks set aside during the week for tackling their assignments. Habit-based schedules for regular work makes it easier to tackle the non-regular projects. It also prevents schedule-busting pile-ups.

- I start early. Sometimes real early. On certain projects that I know are important, I don’t tolerate procrastination. It doesn’t interest me. If I need to start something 2 or 3 weeks in advance so that my queue proceeds as needed, I do so.

- I don’t ask permission. I think it’s wrong to assume that you automatically have the right to work whatever schedule you want. It’s a valuable prize that most be earned. And results are the currency you must spend to buy it. So long as I’m actually accomplishing the big picture goals I’m paid to accomplish, I feel comfortable to handle my schedule my own way. If I was producing mediocre crap, people would have a right to demand more access.

Conclusion

You could fill any arbitrary number of hours with what feels to be productive work. Between e-mail, and crucial web surfing, and to-do lists that, in the age of David Allen, grow to lengths that rival the bible, there is always something you could be doing. At some point, however, you have to put a stake in the ground and say: I know I have a never-ending stream of work, but this is when I’m going to face it. If you don’t, you’ll let this work push you around like a bully. It will force you into tiring, inefficient schedules, and you’ll end up more stressed and no more accomplished.

Fix the schedule you want. Then make everything else fit around your needs. Be flexible. Be efficient. If you can’t make it fit: change your work. But in the end, don’t compromise.

Cal Newport is an MIT postdoc, author, and founder of Study Hacks, the Internet’s most popular student advice blog.